Last time we met, I discussed my winter hiatus and how I’m still a little sluggish from hibernation. Tarot always clears the fog, so I chose the word “breakthrough” from a New Moon in Aquarius newsletter I received last week, lit some sage, clutched my deck, and asked my guides to help a girl out. The card at the very top called to me. I flipped it over and, of course, the Strength card. The next up in this Bonesick series. Kismet synch.

Truth be told, I penned my last story slice—The Chariot, aka The Pale Horse—back in APRIL, dear lord. It’s been a minute. But you don’t have to read and/or refresh your memory. I’m going to change it a bit anyway.

I’m also switching up the structure to save the Tarot card symbolism for the end rather than the intro. Now you can dive right into the good stuff.

You ready for The Upside Down?

8 | The Stray

This time, Box in hand, Toby looked both ways before crossing the avenue that separated his apartment from the city park, the park that would lead him to the bike path, the path that connected him to the WAPT bus line, the line that would carry him to his nearly deserted hometown, the place with the church and the ghosts that separated this pile of bones from the flesh that once was. The entire route would take about two hours. The Box he shifted awkwardly from one arm to the other was not light. But he decided that the discomfort was his mandatory burden on this final pilgrimage to United Methodist.

Toby, The Box, and the bus approached the metro limits and the first of three exits that would lead into town. The sun hung low in the west—a plump, dull red orb that wouldn’t burn your retina if you peeked. Toby gazed down at a used condom tucked behind a seat leg to avoid looking at the charred remains of the Biskit Basket. The diner, along with several buildings in the area, were burnt to a crisp by a pack of arsonists who remained at large. Long before Toby’s employer was a publicly traded global monstrosity, Nüch swallowed up dozens of independent grocery stores, bodegas, and restaurants like the Biskit. The diner was located miles outside the town’s disintegrating center, seemingly protected by a riverway park. Nüch management felt assured the Springer family could continue to run the place, business as usual. But the contagion eventually punctured nature’s barrier. After three too many robberies and one too many dead bodies in a dumpster, the corporate overlords threw a Hail Mary at the problem: abandoned warehouse turned mixed-use condominium. Investments fell through; no one moved in. Rumor had it the series of fires were started by the Springers themselves, but Toby refused to believe they’d do such a thing. Nüch wised up to their capital blunder and opted to go nuclear.

When the WAPT pulled into its terminus, Toby braced himself. United Methodist’s hulking Gothic silhouette loomed in the distance like his father on the porch whenever Toby had returned home well after curfew. He deboarded the bus and shifted The Box to his right hip. It was hard to tell if his arm trembled under the weight of its contents or the memories. He turned down the ghosted Main Street but barely took note of the funeral march of establishments lining each side. Dark, gaping holes that used to be picture windows looked too similar to the cavities Toby refused to acknowledge in the bathroom mirror every morning.

Toby crossed the river that both divided the town and pulled it together. He forced himself to walk past Angela’s old house, boarded up like all the rest. When he rounded the corner with the burned-out ten-story complex that used to be an old folks home, he was punched breathless by the void that unfolded in front of him. He thought he’d prepared his psyche when he’d spotted the death kneel of dump trucks during his previous visit. He hadn’t anticipated the sheer magnitude of the devastation. The entire twelve-block radius that surrounded United Methodist had been completely leveled. What was left of the church structure was the only surviving vestige of a neighborhood once teaming with mothers and mailmen, Sunday cookouts and sunset bike rides. He crossed the sprawl of weeds and rubble, circled to the church’s north end, and scanned the demo fence that diagnosed this cancer as terminal. When a corner of disconnected cyclone revealed itself near a pile of bricks, Toby knelt down, shoved The Box through, shimmied inside the perimeter, and proceeded to the old Community room like a convict surrendering to his warden.

The room’s entrance was wide open—the ornate wooden door likely sold for a mint decades ago, and the stone collapsed around the hole like an old man’s mouth without teeth to give it structure. Stepping over the threshold, Toby was nearly knocked over by the unique stench specifically relegated to abandoned structures like this one. The temperature felt twenty degrees colder, exacerbated by the pungent humidity that emanated from both the surrounding stonework and urine-soaked loam beneath his feet. Toby pulled his hood up against the sour hostility.

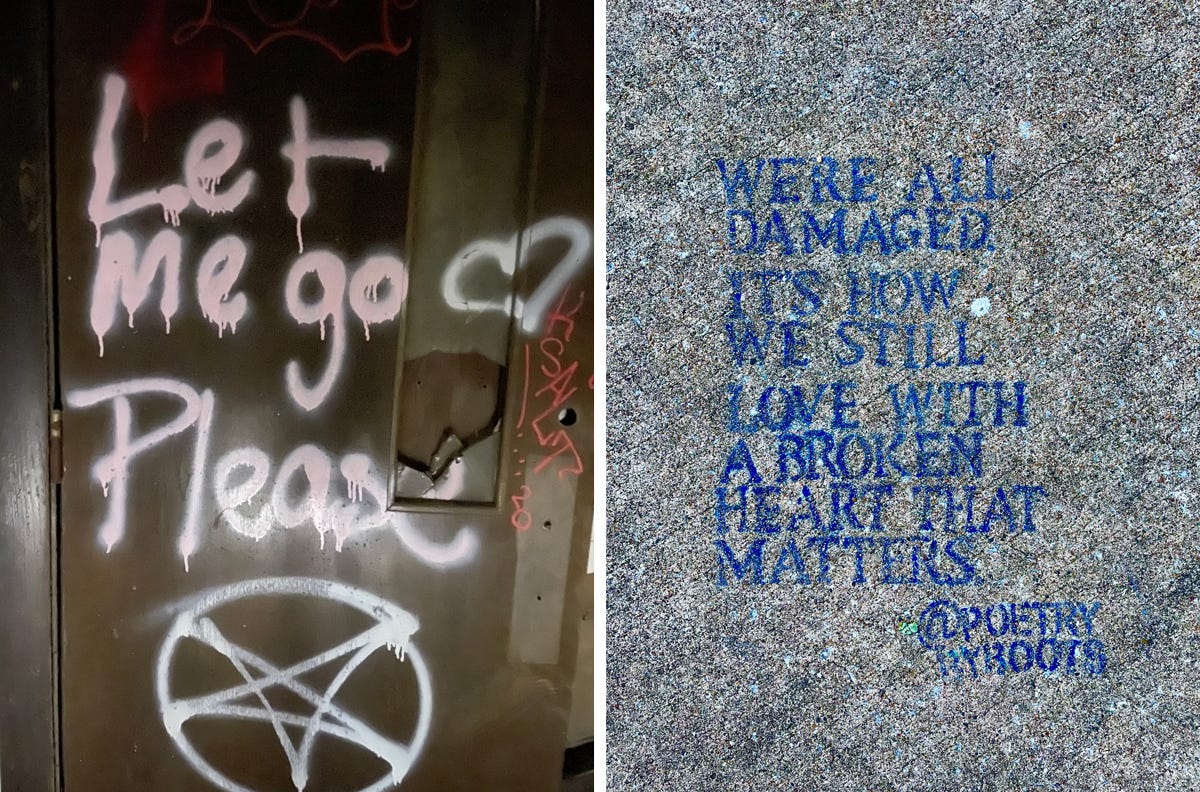

A while back, after the church itself shuttered, some rich philanthropist’s foundation sent a task force to reopen the Community room. The staff turned it into a makeshift donation center, soup kitchen, and shelter for anyone in the area without the means to escape to more lucrative pastures. Toby walked along the seemingly endless piles of refuse that clung to the inner walls. Spongy undulations of dank clothing mixed with building insulation and paperwork spread like a mold bloom. Curious personal items dotted the bleak landscape like shiny bits of candy stuck in mud: one worn tennis shoe with a hi-viz swoosh, a pair of banana yellow six-inch heels, a glass bottle emptied of its bottom-shelf liquor, a packet of stapled pages encrusted with a pea soup substance and marked with an aggressive red letter “D” in the top margin, obligatory drug paraphernalia, a lone five of spades from a deck nowhere to be found, bottle caps with their brands worn off, a shattered cassette titled “Back in the Day” with mangled black tape oozing from one eye socket, a decapitated Barbie doll head, shaved, next to her stark naked body save for the purple plastic purse slung over her shoulder. Graffiti and gang tags coated every surface of the room. “For a good time, call your mom” was written in black marker on a wall next to what used to be the coat closet. “Eat the rich” decorated the refrigerator door. On the tile floor, a stenciled message read, “the broken come back stronger” in the shape of the infinity symbol. And on the cloth partition that separated this room from the church’s main nave area, a spray-painted prayer coupled with a sloppy pentagram: “Let me go. Please.”

Toby’s stomach churned—a bizarre feast for the senses that rendered one both nauseous and famished. He pushed through the partition and entered the sacred space that once cradled his warmest childhood memories. A boy, barely five years old, sat in a wooden pew, surrounded by the familiar pillars of his community. This boy would gaze in awe at his father, a charismatic and verdant pastor who brandished his pulpit like a weapon of truth or consequences. After service, his saint of a mother would stand in the back to exchange pleasantries, dole out comforting embraces, and gather prayer requests. It wasn’t until Toby grew old enough to understand the church’s place in the community—not the heart exactly, but more like the skin, an identity that held their neighborhood together—that he began to see the boils simmering beneath the surface.

When Toby was in elementary school, the seemingly prosperous local plant had closed temporarily and furloughed everyone except upper management. In one of many arguments that punctuated his sleepless nights, Toby heard his father admit to his mother that the church was predominantly funded, not by the weekly offertory baskets, but by the plant. So when the gossip of a permanent shutdown tugged at the community’s fragile fabric, the church was the first to feel the strain.

While they waited for the plant to reopen, families either eyed up the neighboring suburbs that survived on fast food chains and strip malls or aimed for a better shot in the bustling corporate-driven metropolis a half-hour north. After the first union protest, their population’s imperceptible trickle outward shifted to a gushing hemorrhage. As quickly as Toby’s father twisted Bible passages into tourniquets, panicked rumors would rip the words to shreds. In less than a year, the congregation dwindled from thousands to hundreds to dozens. Toby never got to see the last one standing. His father the hypocrite abandoned ship and his mother couldn’t bear to gather anyone else’s prayers when the single request she’d clung to had been ignored. Despite the pickets and protests from workers with more courage in a single throbbing hangnail than the entirety of his father, the plant closed for good. The march for earned sustenance turned into a hunt for table scraps. The threadbare community managed to rally for a little while under a new identity: a cloak of sanguine desperation that preyed upon their naïveté but eventually sucked them all dry. Then the looting began. And the squatting. And the arson.

What remained of those table scraps littered every inch of this cavernous wasteland. With The Box still tucked under his right arm, Toby surveyed the damage. Sconces, statues, pews—anything of value that could be lifted, tugged, or towed was long gone. At some point, the roof collapsed. Debris had rained down like confetti at an exclusive soiree that celebrated the local flora and fauna, which flourished in the grander spotlight.

To his left, Toby found the source of the burning smell that permeated the church, small flames licked the insides of a rusty 42-gallon drum, fed by the broken bones of the once lofted roof. To his right, Toby noticed an overturned plastic shopping cart—a relic of the Before Times when the townsfolk still had consumer choices and disposable income. Underneath the cart, he thought he saw a rounded bulge covered with fur. The bulge looked still, too still. He approached the red cage, and a set of triangular ears confirmed his suspicion—a small cat curled inside. But it was too dark to confirm whether or not it was alive. Someone had trapped it there. Maybe to keep the animal secure while the owner searched for their next meal? Or their next high? What if it was some schizophrenic addict’s idea of a maniacal joke, one last thread of control over an innocent living thing? Toby recoiled at the thought. He put down The Box and reached out to move the cart, but before he could grab a wheel, something else pulled at him instead. Just a few inches from the cart, amongst the dirt and cigarette butts, sat a baby’s pacifier with a cartoon lion on the front, shiny like it had been dropped just moments ago. Toby reeled as his memory strongarmed him back to the evening Angela brought home the dusty pink bag with the powder blue tissue paper. It was a gift from her coworker and confidant from the bookstore, the only other soul they’d told about the fetus growing inside of her. Up to their eyeballs in arguments at this point, Angela reluctantly showed Toby the bag’s contents: a small pack of newborn diapers, a terrycloth bib, and a pacifier with a cartoon lion on the front. All he could muster in response to her display was a curt, thoughtful, and returned to stirring tomato soup on the stove. In dejected silence, Angela stuffed the items back into the gift bag and retreated to the bedroom.

The deafening metallic clink of her door latch startled Toby’s attention back to the pacifier with the lion abandoned to this mess, back to the cart with the cat that could be alive or dead, back to the suffocating remnants of lives collapsed, back to the putrid stench of failure, back to the church with a God that didn’t give a shit about anyone, back to the life that Toby selected instead of whatever it could’ve been or should’ve been.

Toby grabbed The Box and hurled it toward what was once the Sanctuary, but now just a den to shoot up or shoot your load. He located the nearest window and climbed over a heap of busted architecture mixed with shards of stained glass. The moment he smelled fresh air, he emptied the contents of his stomach onto the weeds. But no matter how hard he wretched, he couldn’t eliminate the ravenous apathy that took permanent residence deep inside the folds of his bowels. All that was left of the day was a thin strip of lavender along the western horizon. Toby wiped his jaw, checked the time, and started back. The apartment complex, Angela’s house, the river with the moon swimming amongst the soda cans and plastic bags, the bus, the bike path, the park, the avenue, and the apartment—all lined up like dominoes. Everything felt plastic and colorless, precariously structured. He tried to think of Pam, but even her soft tentacles intertwined in his rigid fingerbones were no match for the hungry sludge that began its feast below. He boarded the WAPT, leaned his skull against the window, and surrendered what remained of himself to the darkness. The insatiable turmoil devoured every last piece.

8 | Strength

They say that we never truly stop being afraid, we just summon enough courage to coexist with that which haunts us. At face value, the Strength card symbolizes the bravery required to meet your deepest darkness face-to-face. But you can keep your muscle-bound, sword-wielding knight in shining armor, chest puffed with a single foot atop the slain dragon. In traditional Tarot illustration, this card features a gentle maiden who cradles the muzzle of a lion in her hands—his gleaming sharp teeth mere inches from her delicate fingers. Our Wild within isn’t something to be slaughtered or even tamed so much as respected, admired, and even perhaps befriended. When you’re this close to a monster that could tear your life to ribbons, you have to commit yourself to understanding your beast fully and completely. You must approach your darkness with unwavering focus and serene compassion. Only then can find symbiosis in the liminal space where civilization meets wilderness, knowledge meets instinct, and order meets chaos. The knight would plunge his sword into the golden heart of the lion and snuff out the flame that could’ve given him a power that goes beyond trophies and kill counts. The maiden demonstrates restraint, wisdom, and patience. The lion regards her with reverence. In time, she builds up the resilience to reach inside and touch the flame. The lion rewards her. Her fear becomes her power.

Next time the mouth of darkness yawns wider. But there’s a light.

References and Synchronicity

Here and in the future, there may or may not be some heavy references to Breakfast at Tiffany’s (the original Save The Cat plot device) only because I love it SO VERY MUCH. Watch these opening and closing clips. Bring Kleenex.

United Methodist is loosely based on the infamous City Methodist Church in Gary, Indiana, here in the U.S. I’ve referenced and illustrated the church in the past here and here, so I updated one of those older comics to feature The Box for this story slice. This piece is essentially my artistic interpretation of the white flight that took down the city once U.S. Steel collapsed—what I imagine it could’ve been like, the loss, anger, and devastation. Here’s an inspiring write-up in the New York Times (February 3, 2024) about where Gary is today and the hope that can blossom when you tear down to start anew. I actually read this article after I wrote this story, and the similarities (the diner, the updated commuter line, the global conglomerate swooping in, the man who’s childhood home is about to be demolished) are truly uncanny. I have many colorful bits of “candy in the mud” that I’ve gathered from Gary over the past 15 years. I do hope that new ideas birth progress and success.

Thank you for reading—I’ve circled over to your desk to tuck a small Valentine that features Garfield enjoying a giant dish of lasagna inside of your shoebox festooned with construction paper hearts. For my practicing Christian friends out there, I see you, and I acknowledge my blasphemous smear upon the brow of Ash Wednesday in my writing here tonight. Trust me, it was all a coincidence! Did you give up something extra difficult this year? From personal experience, coffee was tougher than alcohol. And cheese was tougher than coffee. What about you?

There’s such a pull to hope Toby finds immediate comfort, but there’s also this…maniacal feeling of “yes, suffer…you did this…”

It’s such a contradicting feeling and I fkn love it.

Your writing has such a way of putting me in a chokehold and not letting me go until I recognize the very last period as the end of the piece.

So glad to have you back in my inbox! Cheering for you the whole way!

Yes, yes, yes, yes! Absolute BANGER of a piece! Every time I read your writing, I feel like I'm right there--I can see everything so clearly! I was back in my hometown a few weeks ago. I experienced the same wasteland of deserted retail spots little-me used to beg to go to, so your descriptions of abandonment hit hard.

The phrase that stuck with me: "a bizarre feast for the senses that rendered one both nauseous and famished."